Simon Arthur

"Your heart is where love, compassion and acceptance lie"

Phone: 01263 514642 Mobile: 07757 157013 Email: simon@simonjarthur.com

Thoughts on Grieving

Helping Others with their Grief (Part One)

So, when someone trusts us enough to tell us something of the heartache they are going through as a result of loss, how can we honour that by responding with what they need? Countless books have been written about this, so what follows is not a definitive guide, but a few pointers, from my own years of experience.

- Check your own reaction

Sometimes we can ‘see it coming’ when someone chooses to confide in us, but very often it will come out of the blue – when someone chooses to tell us what they are feeling, it’s usually the result of a lot of soul searching and building up courage, so it can come at unexpected moments. Knowing a little of what to do and say can help us to not feel panicked! So, be aware of how you are reacting and remember to breathe….something we forget to do when we feel off balance.

- Environment

This can be tricky – ideally, we want somewhere quiet, without lots of other people around and where we won’t be disturbed. However, we know that grievers don’t always plan how and when to confide, so it may happen in a crowded place with others nearby. If it is possible to easily move somewhere quieter, that’s great, but not so it’s disruptive and gets in the way. If in doubt, be guided by what the person themselves seems comfortable with.

- How to start

Sometimes people will say they want to talk about what they are feeling, but don’t seem to know how or where to start. So, how do we enable and encourage them? It’s best to keep things as neutral and open as possible – not to impose our own thoughts or feelings on what they may be experiencing. Something along the lines of “tell me what happened?” or “what’s going on for you at the moment?” leaves the door open for them to share as much as they want with us.

- Listen, don’t talk

A golden rule for helping someone suffering the heartache of grief to begin talking is to listen to what they want to tell us. This may sound obvious, but it’s surprising how often we feel the need to ‘have a conversation’ rather than to simply listen. It doesn’t mean that we simply sit silently while someone opens their heart to us, but if in doubt about what to say, then it’s often best to allow space for them to continue.

- Questions are good

Whilst remembering that listening and sitting with silences are generally best, there may be times when you feel it is right to say something – if someone is really struggling to say the words for example. When this is the case, do so in the form of a question rather than a statement. Questions can encourage the other person to continue, to talk more fully about their feelings, to explore what they are experiencing. Statements, or telling someone something, tends to have the effect of closing them down, interrupting their flow or turning the focus to you rather than them.

- Allow silences

Following on from ‘Listen, don’t talk’, one of the most valuable listening skills is to allow silences. We can often be uncomfortable with silence and feel the need to fill the space with words – especially when the subject matter is sensitive and ‘difficult’. However, people who are struggling to speak about the pain of their grief need time to find the words to understand and express their feelings – so give them the space they need.

- Focussed listening

It’s not easy to summarise how to do this in a few words – it’s one of those things that we absolutely know when we experience it. We feel that the other person is fully present with us in the moment and that in some way a ‘bubble’ is created where we can really express our feelings. When we engage with our hearts and commit to hearing what the other person wants to share, then focussed listening tends to follow.

“What is this life if, full of care, we have no time to stand and stare.…” (W.H. Davies)

I’ve seen and heard from so many people for whom one of the effects of the pandemic has been to bring them face to face with past losses and the grief associated with those losses. For some, this has been destabilising, challenging, shattering, frightening, existentially life challenging/ changing. For others it has felt like a new opportunity, exciting, full of possibilities, exhilarating, eye opening. For many, it has been both. That is the nature of really experiencing grief – “the conflicting feelings caused by the end of or a change in a familiar pattern of behaviour”.

I originally thought that so many people being brought face to face with their grief, often for the first time in years, was due to the fact that the pandemic experience can be in itself a loss, and one loss tends to trigger memories, feelings and associations with many other losses. I have worked with so many people who have decided to finally work with their loss and grief issues (from 10, 20, 40 and more years ago) because of a new, and sometimes apparently ‘insignificant’ new loss – which has brought back so many old unresolved ones.

For others, our days have become increasingly occupied, as we busy ourselves with responding to the crisis, - in ‘the front line’, responding to personal and/ or work challenges and helping others to do so. However, in the midst of this busyness, because of what we are busy with, we have also been encouraged (or forced!) to pause and reflect. For many of us, the pause or space we now feel has opened the door to memories and feelings we have kept at bay for many years.

So, what can we do if we are now facing past losses (bereavement, lost relationship, home, career, faith – the list is endless) and all the emotions that come with unresolved grief? Well, we can do what, wittingly or unwittingly, we’ve done in the past and ignore or push them away. There are plenty of ways of doing this – ‘keeping busy’, denying anything is wrong, pushing others away and there are plenty of substances and activities ideally suited to distract us from what our hearts tell us needs addressing – alcohol, drugs, exercise, anger, work, to mention a few. The problem is - and you know this already, that, as powerful as these all may be, they simply don’t work in the long term – they make the feelings go away short term, but they then come back again with more power, more pain, more hurt.

The other way we can approach this is to decide to finally do something about our unresolved feelings of grief. We may feel we are making this decision willingly or it may feel ‘we have to’ – my belief is that the reason why is less important than the fact we have chosen to act. The next huge questions are what do we do and how do we actually face and work with the feelings we are experiencing? We have ‘successfully’ spent years avoiding dealing with these feelings for very good reasons – a primary one being we don’t know how to face and deal with them! If this is the point you have reached – you know things have to change for you – contact me now and we can talk about how Grief Recovery® can help you.

However, whilst this is true in many cases, I am also now beginning to understand that many of us have been brought into close contact again with past losses and grief by the pause in our lives which the pandemic has brought about. What do I mean by pause? For some, this has been a literal pause – we have had more time to sit and think, more time away from what we call ‘normal distractions’, more time on our own.

How Past Losses can come Back

People seem to be recognising that the losses we’re experiencing as a result of the Corona virus are producing grief reactions. The most obvious cause of grief is bereavement, but there are many others, such as loss of job, relationship, money or home. There are also plenty of less tangible losses we can be experiencing right now, such as loss of our future plans or loss of feeling secure. They may be less obvious, but can be no less powerful in their effects.

So, what can this grief feel like? People talk to me of feeling a general sense of heaviness they don’t normally experience, or of feeling abnormally tired, lacking concentration or any of the many other symptoms of grieving. For me it’s good news that more of us are now recognising what we are experiencing as a grief response.

So what’s happening here? When we experience a significant loss and are not able to deal with it, because we are not given the right tools or help, the unresolved grief we experience does not simply go away. Time, despite popular folklore, is not “a great healer”. All that time does is pass. If we do nothing to address our unresolved grief, it will continue to hurt us, to hang around.

However, I’m being contacted by people who certainly recognise the losses around them, but cannot understand why their grief reaction is so extreme. They describe this as being ‘overwhelmed’ or ‘swept away’ by a tidal wave of pain and heartache, of a breakdown or crisis with feelings of deep despair and hurt. In addition to coping with these feelings, they also ask themselves “Everyone’s going through this – why am I not coping? ….Why am I being so weak when others are managing OK?” Unsurprisingly, as a result they feel worse still. When we talk a little more, I usually find that they are not just facing grief over present losses – they are also trying to deal with the pain of unresolved grief about past losses – often many losses and from many years ago. It’s not surprising that they are feeling overwhelmed and at crisis point.

We may mistakenly believe we have dealt with it, because we block it, pretend it doesn’t exist, close down parts of our lives or memories. However, the unresolved grief will come back – most often when we face new grief – such as through losses from the Corona virus. In this way we can ‘stack’ a whole pile of unresolved griefs, that then come back to us or crash down on us when, sometimes years later, we experience a ‘trigger event’.

So, until or unless we take active steps to recover from our unresolved grief, it will come back to hurt us and cause us heartache. Those of us experiencing an ‘overwhelm’ of these feelings are not less resilient or overly sensitive – simply experiencing the effects of unresolved grief from multiple losses over time. The Grief Recovery® programme enables us to recover the pain of unresolved grief and so breaks this cycle of us unwittingly building a ‘tower’ of unresolved grief.

Circular Thinking

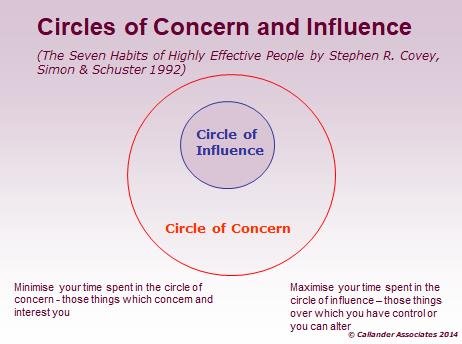

Stephen Covey knew a thing or two. I’ve lost count of the times I’ve used his ‘Circles of Concern and Influence’ model in my training, mentoring, management, leadership and one to one work over the years. We can either commit our energy to things that concern us (world poverty, the global environment, social injustice) or things that we can influence (living more sustainably, actively supporting those in need, living with care and compassion). We can expend energy and time talking about what “someone should do” or get on and do something ourselves. The more time we spend in our circles of influence, the more effective we become – partly through not wasting time and energy on what we cannot change and partly because we get better at influencing. We can use the model as individuals, groups or teams, localities, political or economic groupings, countries……the list is endless.

It’s struck me in the last couple of weeks that, individually and collectively we have done much to shift our energy from concern to influence. So much of the Corona virus strategy is based on circle of influence – physical distancing, buying what we need, looking after others. Many of us are experiencing a tangible shift in the focus of our lives – doing what we can to improve things for us all, not just ourselves. In the midst of the shock, fear and trauma of the pandemic, there is also a real sense of possibility for making a genuine difference for ourselves, our communities, our country and our world through spending our time in our circles of influence.

Pope Francis also knows a thing or two. In his Urbi et Orbi address last Friday, he spoke of judgement – what we call ‘God’s Judgement’ and our own judgement. He said that this time is not one in which to focus on ‘God’s Judgement’, but on our own judgements: “a time to choose what matters and what passes away, a time to separate what is necessary from what is not.”

In the coming weeks, months and years we have an extraordinary opportunity to make judgements – do we maintain and re-commit to care, compassion and action to help others, or do we return to a more insular and self - focussed circle of concern?

Helping Others with their Grief (Part Two)

And now, for some ‘what not to do’s’:

- Don’t tell others!

This is a fairly obvious one, but it’s important that not only we know that what is being said is confidential, but that the person talking about their feelings also knows this is the case. Giving them a sort of ‘confidentiality statement’ could feel a little strained, but do be sure they know you won’t be speaking with others about what they tell you.

- Don’t try to cheer people up

Sometimes this actually comes from our own discomfort at someone else’s distress – we want them to feel better. Phrases like “don’t worry” and “it could be worse” don’t actually help - be assured that the most effective way to help someone change their mood is simply to let them know that they have been heard by someone who cares.

- Don’t advise

We can often feel tempted to give people helpful advice on how best to deal with what they are going through. Usually when they choose to talk about their feelings, they are not after advice – what they want most is someone who cares to hear them. When we offer advice it also tends to steer attention away from what the other person is feeling and towards the experience of the advice giver – the focus needs to be on them, not us.

- Don’t compare

This one really goes with ‘Don’t advise’ – we can say things like “I remember when my Dad died….Julie went through the same thing after her daughter died”. Again, the problem is that this takes attention away from the griever – we may be trying to establish some common ground and to say that we understand, but the effect is to cut across what the griever needs to share with us

- “I understand how you feel”

Please don’t say this for two very good reasons. Firstly, it simply is not true – each loss is experienced uniquely - we may have experienced a loss similar to the person speaking with us, but we cannot understand what the other person is feeling – their feelings and reactions to their loss theirs alone. The other reason not to say this is that it also takes the attention away from the griever and back onto the person saying they understand. This time is for the griever and their feelings.

- No helpful tips

“When I lost my Mum I found the best thing to do was….The first 6 months are always the worst….” This is another version of ‘Don’t advise’ - it’s almost always not what people want or need when they choose to confide in us and it takes away attention from them and onto us.

- Physical contact

When someone opens their heart to us to speak of the pain and heartache of their grief, a natural human reaction is to reach out to give them a hug or to simply touch an arm or shoulder. This can be helpful, but we also need to ask some questions of ourselves as well. Firstly, who is the hug or touch going to help? We need to be sure that it is what the other person wants – if needs be, ask them if they want a hug. Another thing to be cautious about is that any physical contact can break the flow of someone opening their heart to us – it’s not the intention, but usually once someone has started, its best to allow them to continue till they are ready to stop.

- What next?

Having shared their feelings and thoughts about their grief with us, someone may say or ask what they should do next. As, before it’s best avoid the temptation to offer advice or to get into comparing. “What do you think would help you most now?” can be one question to ask. They may know the answer, but even if they don’t, a question like this can open the way to explore further. If the person doesn’t raise the ‘what next’ issue, it can be useful to ask them – they may say “nothing” or come up with something practical (go for a walk, have a coffee) or something much longer term. Any of these are fine – the key is that you are responding to their need in that moment.

- Offer to listen again

More accurately, I would describe this as ‘suggesting’ that you meet again to listen some more. A common feeling amongst people who have started to talk about their feelings (along with ones of relief, lightness and tiredness) is that of guilt at having ‘burdened’ the listener. Because of this, they may find it difficult to ask to meet again, or to say “yes” if we simply offer to listen again. So, I’d recommend that you suggest that the two of you meet again to talk, as long as this is something they would find helpful. If they are sure they don’t want this, that’s fine, but leaving it up in the air by saying something like “do get in touch if you want to talk some more” puts the onus back on them in a way that may not be helpful.

- Listen with your heart

This final point really informs and runs through all the others and is probably the most important of the lot. People often say to me “I don’t know what to say….I don’t want to get it wrong”. The truth is that we will all get it wrong sometimes. The key here is that if we are present with the other person with our heart open and they experience this, mistakes don’t matter. They will know that we are there for them and to help them and any mistakes in what we do or don’t say or do simply don’t matter against that background.

Bereavement and ‘Ambush Moments’

We can be listening to a piece of music or song, tasting a particular recipe or item of food, someone who looks just like…., hearing special words spoken or suddenly be aware of a particular smell and immediately, bang!, we are overwhelmed with a huge rush of sadness, joy, loss, a certain memory, deep pain, laughter, or possibly all of these, and more.

I would guess that pretty much everyone who has experienced the loss of someone they have loved and the resulting grief will also have had their feet swept from under them by an ‘ambush moment’.

One of the strange parts of ambush moments is that they’re not always negative feelings that we experience – they can manifest as warm and loving feelings – often with laughter and broad smiles. We know the feelings are absolutely connected with the person we have lost and that they are hugely powerful and come as a shock. Usually we don’t immediately know how or why this particular sight, sound, smell or other sense has affected us so deeply. We’re too busy dealing with our physical reactions to these ambush moments.

The strength of the feeling can be shocking in its intensity – we are often left literally gasping for breath by the strength of the ambush moment, as well as feeling confused and sometimes frightened at where the feelings have come from and why they feel quite so powerful. Painful ambush feelings, such as loss, yearning, loneliness and abandonment can feel especially devastating and, even if we can’t do so at the ‘point of ambush’, we need to talk through and get support from someone we trust with our vulnerability.

We’re often surrounded by other people when having ambush moments and the sudden breathless tears, smiles, laughter and/ or sobs are difficult for us and them to deal with. We can end up feeling embarrassed at best and unbalanced or slightly deranged at worst – we should be able to control our feelings, surely?

The good news is that there is nothing wrong with having ambush moments and that they may actually be a good thing. After we lose someone (or some thing – they don’t just apply to bereavement, but also to all sorts of other losses – such as health, job, relationship, faith, home), consciously and unconsciously we put strategies in place to cope with the pain of our grief. We might ‘keep busy’, steel ourselves to ‘be strong’ for others and for ourselves, or we might drink more alcohol/ food or any one of numerous other behaviours we turn to at such times. There is nothing inherently wrong with many of these strategies – some may help us to cope initially. However, they can all have the effect of keeping us away from our real feelings of loss, or at least from the true strength of our feeling. The feelings we experience during ambush moments have no such filters – we feel the feelings full on, with defences or barriers in the way – that’s why the effect is so breath-taking and overwhelming. So, although ambush moments can be somewhat startling, we can be sure that what we feel is real, both in the type of feeling and in its intensity. We are having the full fat version, unmuted by our rationalisations and strategies – and this applies for sad or painful feelings, or the joyful, funny and warm ones that can ambush us – we can often feel several hitting us at once or in quick succession. Would we really want to edit or blank out such feelings? It could be exhausting to feel them all the time, but to experience them full on is testament to and proof of the relationship we had with the person or thing we have lost.

So, the next time you have an ambush moment, think about welcoming it as a true messenger of your feelings about what you have lost.

How to show True Courage in Grieving

I seem to listen to the radio mostly when driving from place to place these days. Whilst it makes my journeys seem shorter, it does have the annoying effect of picking up snippets of really good stories without knowing the full context. Last night, for instance, I heard a programme about a young former army officer who had lost his leg in an IED attack in Afghanistan and who has gone on to do amazing things.

When we think of ‘courage’, many of us immediately think of some sort of extreme, traumatic event, often with military/ violent overtones. I used to think that courage was something to do with a sort of flinty eyed, chisel jawed refusal to be afraid and battling through insurmountable odds.

The headline for the programme was about the fact that he regularly rides as a jump jockey, but what I (and he) found really interesting was the inspiring work he did with a whole range of people in this country and abroad, using his leadership and motivational skills. His matter – of – fact description of his injuries, subsequent recovery and the way he chooses to present and ‘frame’ these got me thinking about the nature of what we call ‘courage’.

I now see true courage as being very afraid, but doing the right thing anyway - a very different virtue and a very different process. For example, in my Grief Recovery® practice, I have seen huge courage in those with whom I have worked.

.

The first part of that courage comes in picking up the phone and calling me for the first time. To recognise not only that we are not coping, to reach out for help and make ourselves vulnerable like this not only takes a great degree of trust, but also of courage. I am truly humbled and feel privileged to work alongside the people I see who have this (and many other) type of trust and courage.

One of the Six Myths of the Grief Recovery Programme® is “Be Strong”. We are subtly (and sometimes not so subtly!) taught, told and led to believe that ‘being strong’ for ourselves and others when faced with bereavement and other losses is a great virtue and will help us and others through these challenges. I certainly applied this myth myself for many years. I was so busy trying to ‘be strong’ (in much the same way as my early views of courage – see above) that I ended up burying and effectively denying my own feelings of loss and grief, with inevitable pressure cooker results. I’d describe this as ‘Be Strong Version 1’.

There is a sense in which we can ‘be strong’ in a way that is helpful to us and others after a major loss, but it is a strength of allowing ourselves to be vulnerable, being honest about our feelings and allowing and encouraging others around us to do likewise (‘Be Strong Version 2’). In order to accept that our grief is the natural and appropriate response to the loss we have experienced, we need to fully experience the grief, just as we fully experienced the relationship with the person or thing we have lost. It’s not self - indulgent or mawkish, just plain good sense and critical if we are going to assimilate the loss with all the other parts of that relationship.

In my work with bereaved children, I often see the effects parents and carers can unwittingly have by using ‘Be Strong Version 1’ to help their children through their loss. Of course it doesn’t help the children at all – they get the message that strong feelings are scary things to be avoided at all costs, that shutting down our emotional selves is what works, that they can’t talk about what they feel because “we have to ‘be strong’ (Version 1) like Mummy, Daddy, Grannie, Grandpa…..” and, above all, they also learn the lesson that this is the way to deal with our grieving – and so it passes to the next generation.

In bereavement and other losses, as in all things, true courage lies in experiencing fear and doing the right thing anyway – it’s not easy, but it wouldn’t be courage if it was, would it?

Losing your Pet

Tom felt like his heart was broken. His much loved dog Charlie had died 3 months ago and he had felt lost and hurting since then. He missed everything about Charlie – the fact that she was always so excited to see him – even at the end, their walks together and the solid pressure of her on his side when she lay on the sofa with Tom and his wife.

upset Sandi. He probably meant well, but Tom had been shocked at his lack of understanding and so simply closed down on the subject from then on. Tom knew that he was eating and drinking more than he should – but it seemed to stop him feeling the loss so much.

Tom and Sandi had agreed to put way Charlie’s collar, bowl, lead and numerous toys after she died, but they had said little else to each other about losing her. It was as if neither could bring themselves to raise the subject – it was just too painful and Tom didn’t want to

In his heart he knew that he was simply blocking the pain – it always came back again. As he lay awake at night, tired but unable to sleep, the unwanted thoughts and feelings played through his mind – of the day Charlie died, the vet saying that there was no real alternative but to put him to sleep. Sandi had been too upset to say yes to this, so Tom had to and now he felt guilty for agreeing to their dog being put down. His head knew it was the right thing to do, but his heart still ached for the time he held Charlie while the vet was giving her the injections.

Questions ran through his sleep deprived brain – had he really dealt with losing his Mum or his sister in law. Was he going crazy, feeling like this about a pet dog?

Eventually Tom went to see his GP and told her what he was feeling. She listened carefully and suggested he try a course of anti – depressants, but even as Tom left with his prescription, he wondered to himself if this was simply a lie advising him to eat or drink more to keep the pain away.

It was then that Tom called me – he later told me that this was one of the most difficult calls he had ever made in his life – and also one of the most important. I work with people who feel as though their hearts are breaking because of a loss or losses. It is often bereavement that prompts people to contact me, but it can also be one of many other losses we can experience – loss of relationship, career, home or faith to mention a few. When I say ‘heartbroken’, I don’t mean the sadness immediately following a loss, but a deep and lasting feeling that seems to take away the ability to truly feel or enjoy what we once found good, feeling untouched by what once made us happy or feeling emotionally closed down and not looking forward to the future. It can also mean that people get ‘stuck’ in the loss itself – they don’t feel able to experience emotions other than those from the loss itself, or they find it difficult to speak at all about the person or thing they have lost.

Tom later told me that whilst talking to a complete stranger about his feelings felt incredibly hard to do, it also felt as though a weight began to lift from his shoulders and that he was able to say things that he never could to those he knew and loved.

I work with people using the Grief Recovery® method. It provides information about loss and grieving that dispels many of the unhelpful myths that can actually harm and hinder our grieving. It then provides a series of steps that not only help us to identify the source of our unresolved grief, but also the way to move through this to start living our lives fully again. Many counselling and therapeutic approaches are good at helping us to see why we feel as we do, but do not then give us a way forward. The process is, not surprisingly, emotionally challenging, but feels safe and achievable as I provide confidential support and guidance throughout.

So, what of Tom? He has completed the programme and, as he suspected, it not only helped him deal with the loss of Charlie, but also to work through the loss of his mother and sister in law. He is able to talk about Charlie to other people now – the happy and funny memories as well as the sad ones. He has felt strong enough to talk with Sandi about his feelings and. They may get another dog and they’ll wait until they know whether it’s the right thing to do – the decision isn’t a problem anymore.

They’ve talked about other losses and for the first time in months, maybe years, it feels like the barriers are down and OK to talk openly and honestly. Above all, Tom is looking forward to the future – each day has possibilities and hopes for him again.